Broadening our Horizons: From Migrant Mental Health to Transnational Families’ Mental Health26/7/2022 By Dr. Astrid Escrig-Pinol

Last fall, the United Nations World Mental Health Day’s theme was “Mental Health in an Unequal World”. Mental health inequities, locally and globally, clearly reflect poverty and disparities due to race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity. By highlighting inequality, the World Federation for Mental Health underscores the need to address discrimination and inadequate quality in mental health services, worldwide. A population group disproportionally affected by poverty and discrimination are international migrants in low-paid jobs who experience a higher risk of social isolation and often face structural barriers that prevent them from accessing mental health services. At the same time, families left behind in their countries of origin face emotional and social challenges resulting from the need to restructure relationships and roles when a central actor in the family unit is absent for prolonged periods of time. Family separation is a common result of many regulated and unregulated migration pathways. Obstacles to move as a family are much more common for families at the lower end of the socio-economic range, who move out of dire need with limited rights and mobility, than for those at the higher end of the income scale. Imposed family separations are a source of suffering for so-called transnational families. Clearly, migration is a family affair that has consequences not only for those who move, but also for those left behind. The mental health of migrants’ left-behind children, parents, siblings, and extended family members is inevitably affected by the coming and going of their relatives. By broadening our focus from the mental health of migrants to the mental health of transnational families we can understand how inextricably connected they are. To effectively address the impact of migration on the mental health of people on the move, in particular low-paid workers and their non-migrating families, we need to look beyond national borders and think in terms of transnational public health research, programs, and policies. Astrid Escrig-Pinol, PhD Associate Professor, ESIMar (Mar Nursing School), Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Research Associate, SDHEd (Social Determinants and Health Education Research Group), IMIM (Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute), Barcelona, Spain [email protected]

0 Comments

Moving beyond Reactive Responses to Human Trafficking: The Potential of a Public Health Approach14/9/2021 By Dr. Liz Such

I believe it is time for international responses to human trafficking to be pro-active and oriented by public health. We can learn from practitioners and researchers in different regions to create more effective responses. For instance, in the ECHOES blog published in July 2021, Hari and Salami helpfully explore how health services and providers can respond to the needs of people who have been internationally trafficked and exploited in North America. In the UK, the evidence base has been developed through seminal works such as the PROTECT study; practice has been improved through health professional networks such as VITA; and professional bodies such as the Royal College of Nursing have produced guidance to support victim detection, referral and treatment. These are important steps in the battle to address the exploitation of migrants and other communities living in vulnerable circumstances. But as we respond to the problem as we encounter it, practitioners have realized the importance of shifting their attention further upstream, towards the wider contribution the health sector can potentially offer to the prevention of harms. In other words, our focus has moved to stopping the worst from happening. Thinking about prevention in the UK is being greatly influenced by the long-established principles of public health. These include, ‘zooming out’ to see the problem at a population level, identifying opportunities to intervene, focusing on improving health, well-being and more equitable outcomes, using data and evidence to explore ‘what works’ and working in an interdisciplinary and multi-agency fashion. Indeed, the UK’s Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, alongside other statutory bodies, has endorsed the development of a public health approach to human trafficking. This has been developed in a UK context by our team at the University of Sheffield and alongside the Commissioner and Public Health England. We have co-produced a public health framework and a guide for policy, practice and local anti-slavery partnerships. This progress has the potential to re-frame discussions about human trafficking prevention away from awareness raising and criminal prosecutions and towards intervening across cycles of exploitation risk and harm along the migration journey. These materials are available to explore at this microsite. As a co-produced resource, it is regularly updated and developed as we receive feedback. We welcome all contributions to how a public health approach can be further developed and mobilized. Please contact the author with your feedback and questions. Also, please contact Dr. Frances Recknor, in Toronto, if you have ideas or questions related specifically to public health and human trafficking in Canada. Together we can prevent human trafficking and act to dismantle its root causes. Liz Such, PhD Research Fellow, University of Sheffield and Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellow, National Institute of Health Research, UK [email protected] Contact in Toronto: Dr. Frances Recknor, [email protected] By Cayla Hari and Professor Temilola Salami Human trafficking is a form of slavery and an egregious human rights violation where victims are exploited through means that involve force, fraud, or coercion. The two most common forms of trafficking are labour trafficking and sex trafficking; however, other forms include organ trafficking, forced criminal activity, and debt bondage. Victims often face physical and psychological health concerns as a result of being trafficked. Physical and mental health symptoms persist even after victims have escaped their abusive situation. In 2000, the United Nations established the Palermo Protocol, which was designed to prevent, suppress, and punish the trafficking of individuals. The Palermo Protocol led to a global increase in the awareness of trafficking, as well as research and funding devoted to trafficking awareness. Although human trafficking occurs both amongst native-born and foreign-born persons, stakeholders invested in the health and wellness of human trafficking victims need to note additional considerations for foreign-born victims. Persons who are in the process of immigrating to, or who have recently immigrated to North America are vulnerable to exploitation by traffickers. Foreign-born victims must navigate unfamiliar customs and laws, new surroundings, and language barriers, which increase their vulnerability of being trafficked. Traffickers are aware of the social and economic adversities victims face and use these circumstances to exploit victims. For example, immigrants escaping adverse circumstances may be coerced into paying high immigration and transportation fees and become indebted to traffickers. Upon immigration, victims may be unwilling to report traffickers for fear of deportation. In addition, foreign-born victims may be at greater risk of negative mental health outcomes as their trafficked experience is often compounded by immigration stress. As foreign-born victims come from diverse socio-cultural contexts, their experiences of trauma and psychological distress may differ and be amplified by the intersection of multiple distressing circumstances. To provide the necessary support for victims, stakeholders invested in victim advocacy and care must consider the unique experiences of their clients. Specifically, health professionals could use an ecological framework, which emphasizes the importance of assessment and care at varied and interconnecting ecological levels (i.e. individual, interpersonal, community, and societal). For example, healthcare professionals should focus on understanding the unique identities of their clients at the individual level, help facilitate communication with social supports at the interpersonal level, facilitate victim identification training programs at the community level, and engage in advocacy at the societal level. A recent publication by Salami and colleagues (2021) provides a more detailed discussion of these considerations among foreign-born victims. These recommendations serve as a starting point for providing comprehensive care to foreign-born victims of trafficking. In order to further assist victims, we propose research about human trafficking among foreign- born victims be expanded. To maximize the efficiency and comprehensiveness of service provision, there is a continued need for research on victim identification, validated and effective training programs and tools, and research that can aid the awareness and reduction of mental health stigmatization among foreign-born victims. Cayla S. Hari

Doctoral Student Department of Psychology and Philosophy Sam Houston State University Huntsville, Texas Professor Temilola Salami Assistant Professor Department of Psychology and Philosophy Sam Houston State University Huntsville, Texas By Professor Patricia Landolt

Making the case for Health for All requires a powerful and irrefutable storyline. This is the work of cultural politics. In Canada, the cultural narratives mobilized to extend access to healthcare for precarious legal status migrants are ambiguous. They help secure short-term and strategic gains, but they fall back on liberal nationalism to make the case, obscuring the essential links between human rights, mobility rights, and healthcare access. Globally, pathways and access to citizenship are increasingly restricted. The human rights of ‘people on the move and out of place’ have been eroded. In Canada, this takes the form of a two-track, two-step immigration system that prioritizes temporary migration. The immigration system also continually produces people out-of-status. All temporary migrants have precarious legal status. They are deportable and there are legal limits set on their access to work, healthcare, and education. Mapping Cultural Narratives of Access Access to healthcare for precarious legal status migrants is a battleground in the fight for human rights and mobility rights. I interviewed Health for All advocates in Toronto to understand the cultural narratives of healthcare access. Frontline healthcare workers juggle three narratives of access:

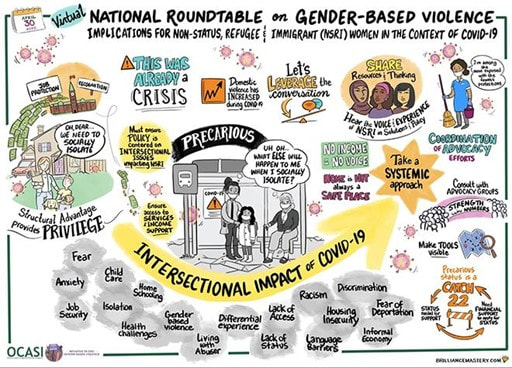

Healthcare managers prioritize risk management and fiscal efficiency. They emphasize preventive healthcare as a cornerstone of the medical system. Access ensures migrants will not wait till a health need turns into a costly medical emergency. Policy-change advocates focus on legal and human rights. They make value-laden links between the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Canada Health Act, and the 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Advocates deploy these narratives in variable combinations to advance their agenda. Community health workers find procedural wiggle room in existing regulations, stretching eligibility criteria for specific groups. Resource limitations and partnerships with hospitals impose access restrictions based on categories of immigration status. This usually means no visitors or international students. Time in Canada and vague ideas about a migrant’s ‘intention to stay’ become the discretionary filters for health access. Policy work tends to be strategic and opportunistic, focusing on winnable issues that align with other drivers of the health care system. It prioritizes the extension of health insurance to citizens-in-waiting and leaves other categories of temporary migrants out. On the frontlines, in hospital and clinic management, and in policy-work, the cultural politics of healthcare access fall back on a normative attachment to Canadian citizenship—as likelihood or ideal. This sets limits on how migration is understood, migrants are imagined, and health deservingness is practiced, resulting in the erosion of the links between Health for All, human rights, and mobility rights. Patricia Landolt Professor of Sociology University of Toronto By Professor Rupaleem Bhuyan and Margarita Pintín-Pérez On March 8, 2021, millions of people around the world will mark the 110th anniversary of International Women’s Day by organizing for gender equity and women’s rights including those who identify as lesbian, bisexual, trans, and/or queer. In the spirit of the IWD2021 campaign theme, #ChooseToChallenge, we highlight the call from migrant leaders to challenge systemic inequalities in our social, economic, and health care systems that are fueling the syndemics of COVID-19, gender-based violence (GBV) and systemic racism facing non-status, refugee and immigrant women. In their commentary published in BMJ Global Health, Stark et al (2020) argue that “the drivers and impacts of COVID-19 and GBV do not occur in isolation; rather, they present as a syndemic—each is made more destructive by the presence of the other.” Although risk of illness from COVID-19 does not increases the risk of GBV, our public health and economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic have only magnified long-standing inequalities for racialized migrant women leading to higher rates of COVID-19 infection, loss of life, and more severe cases of gender-based violence (Scotten, 2021, February 11). In Ontario, immigrants and refugees comprise about 25% of the total population but have accounted for 44% of all positive COVID-19 cases (ICES, 2020). Furthermore, the majority of front-line health workers and care workers are racialized migrant women from the Philippines, Jamaica and Nigeria, whose health and economic risks are magnified due to their precarious work and the lack of paid sick leave or unemployment insurance (RNWSN, 2020). Accompanying economic strain, social distancing measures, and fear that seeking help will lead to deportation or losing custody of one’s children further endanger migrant women, including refugee claimants, international students, temporary workers, and people without status, who are isolated with abusive partners, family members (Violence Against Women Learning Network, 2020), or employers. As Caregivers Action Center (2020) detail in their report “Behind Closed Doors,” many domestic care workers have lost their jobs or have faced increased abuse and exploitation during the pandemic. Early on in the COVID-19 Pandemic, grassroots leaders and service providers came together for a National Roundtable on Gender Based Violence to discuss how migrant women and people without status were already “in crisis” before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic due to lack of access to vital health and social services, fear that contacting the police would lead to arrest, immigrant detention, or losing custody of one’s children, and their dependence on family members or their employers to maintain their legal status in Canada (see illustration of the roundtable discussion below). OCASI Initiative to End Gender-Based Violence (2020, April 30). Virtual National Roundtable: Gender-Based Violence against non-status, refugee and immigrant women in the context of COVID-19. Toronto, Ontario. https://ocasi.org/gender-based-violence

Towards challenging isolation and exclusion, roundtable participants emphasized the need to centre the lived experience of migrant women whose concerns have been too often overlooked in the public health and economic responses to COVID-19 and GBV. WORKING TOGETHER TO DISMANTLE STRUCTURAL INEQUALITIES Well before the COVID-19 pandemic, grassroots migrant leaders and advocates across Canada have been calling attention to structural violence produced through Canada’s immigration policies and systemic racism in Canada’s labour market. During this time of increased alertness, it is imperative that we listen to, learn from, and support migrant-led advocacy campaigns to address inequities in our economic, social welfare, and immigration systems to ensure basic human rights, but also to protect our individual and collective well-being. There is no more time for careless oversight. We must #ChooseToChallenge systemic inequalities that are fueling the syndemics of COVID-19, gender-based violence, and systemic racism. The way forward is clear and within reach, if we stand together. SUPPORT ECONOMIC & LABOUR CAMPAIGNS

ADVOCATE FOR FULL & PERMANENT IMMIGRATION STATUS NOW!

Rupaleem Bhuyan, PhD Associate Professor Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work University of Toronto Margarita Pintin-Perez, PhD, MSW Senior Coordinator, Initiative to End Gender-Based Violence OCASI- Ontario Council of Agencies Service Immigrants By Professor Janet McLaughlin

COVID-19 has exposed and at the same time worsened many preexisting inequities. Invisible to most Canadians prior to the pandemic, migrant agricultural workers from countries like Mexico and Jamaica, who labour in Canada on temporary contracts, gained national and even international media attention this year, but for all the wrong reasons: they were disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. With well over 1,600 workers infected and three deaths, agricultural workers are among the most widely impacted groups in Canada. What makes this grim reality both tragic, and infuriating is that this was predicted. In early spring of 2020, my colleagues and I formed the Migrant Worker Health Expert Working Group to raise awareness about the vulnerabilities that migrant workers faced in the context of COVID-19, and to make evidence-based recommendations to all levels of government to improve their health and safety. Based on decades of research and clinical work, we warned that migrant workers would be particularly at risk. They lack full protections at work, fear losing precarious jobs with tied temporary work permits, and face numerous barriers to health care. With dozens of workers often sharing cramped living quarters, when infections occur, they can spread like wildfire. That’s exactly what happened. All three of the workers who lost their lives to COVID-19 in Ontario were from Mexico; all were relatively young, and all were here to grow our food and to support their families. The first to die was Bonifacio Eugenio-Romero at 31-years-old. Bonifacio was self-isolating in a hotel when his condition deteriorated. He died shortly after calling for emergency help, his final moments spent alone. He had no previous health conditions. Unsettling questions remain over whether he would have survived had he received more supports, such as regular check-ins by health officials, which could have led to earlier medical interventions. Juan López Chaparro was a loving husband and father of four who died after over 200 workers were infected with COVID at his place of employment, Scotlynn Group. The bunkhouses at this farm held some 70 workers per unit. He died at the age of 55 after a decade of working in Canada. Rogelio Muñoz Santos was just 24 years old when he died. He was an undocumented worker, who labour advocates believe could have been a victim of human trafficking. Rogelio and his co-workers were placed in overcrowded housing and not provided with information about how to protect themselves from COVID-19, or the equipment to do so. The conditions that led to these workers’ deaths were neither inevitable nor unforeseeable. It is time for us to show we value those who produce the food we eat and protect migrant workers’ lives and health as much as we do our own. We need immediate action to reform policies surrounding migrant worker programs to ensure they provide these essential workers with safe and dignified living and working conditions, full access to rights and protections without fear, and the option to change employers and ultimately to become permanent residents. No more workers should be placed at a position of peril in Canada. Janet McLaughlin Associate Professor of Community Health, Wilfrid Laurier University Research Associate, International Migration Research Centre Co-coordinator, Migrant Worker Health Project & Migrant Worker Health Expert Working Group Beyond Basic Needs: Fostering Intentional Spaces for Migrant Children's Voices and Identity3/6/2020 By Wendy Young and Jasiel Fernández

As he described the ordeal that was his trip from Honduras to the US, I saw a sparkle of wonder deep in his eyes. His young 17-year-old face, that had had its shares of experience far beyond his years, slightly wrinkled as he smiled. “While waiting to hop on La Bestia [the infamous migrant train through Mexico], I saw a boy playing with toy cars in the dirt. I sat playing with him for hours like I too was 8 years old, como un niño. Maybe it’s because I never had any toys, but I felt so good that day, I felt like I stopped time.” Under the current climate, migrant children’s protections erode in rapid fire fashion with minimal time to address the deeper, foundational issues affecting the child. In our roles as passionate advocates focused on protecting and caring for children, we run the risk of ignoring that children have individual identities worth preserving. Children’s idea of self is primarily predicated on their sense of permanence and attachment. As practitioners supporting migrant children in their journeys, and advocating for their basic legal rights, we find ourselves indirectly preserving their sense of personhood and ethnic/cultural wealth. By prioritizing indigenous language support or appreciating cultural diversity through a responsive lens, practitioners become first responders in fostering a sense of permanence for migrant children, establishing a possible life-long deposit to their notion of self and belonging. The interdisciplinary model espoused by Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), focuses on safeguarding children’s legal rights as much as their individual dignity, recognizing that as advocates we support clients’ permanence and attachment on multiple fronts. While we help our clients navigate the maze of paperwork and procedure that characterizes our immigration system, we become witness to the unfolding of existential journeys of many. Migration comes with an inevitable dose of grief and loss, especially for children. As detailed in the article, “Impact of Punitive Immigration policies, parent-children separation and child detention on the mental health and development of children” migrant children, especially those in detention facilities, experience marked disruption in their attachment with increased levels of toxic traumatic stress. In our continuous task of advocating for due process, protection, and care, we amplify their trauma, lack of opportunities, and bleak statistics. While we cannot negate the impact of the inhumane targeting of migrant children, strictly following the advocacy vortex, however, can undermined the inspiring resilience, sense of identity, and deep connection to community that migrant children bring with them. Host countries welcome invaluable potential when migrant children receive support, nurturing, and encouragement to thrive. As supporters of migrant children, do we commit to bringing parity in our portrayal of immigrant communities? Do we espouse a culturally responsive, strengths-based approach recognizing that vulnerability and strength do not constitute mutually exclusive concepts? Do we make space for immigrant children to amplify their own voices? Social determinants of health encompass many aspects—migration certainly becoming a very salient one. It is ever so critical to support migrant children’s rights, access to safety and care in increasingly more determined ways than ever. The genius centers on doing so while recognizing the immense wealth, potential, and dignity of those on whose behalf we advocate. Strengthening connectivity toward multi-disciplinary support for migrant children and their caretakers provides a long-term investment in permanence. As practitioners, we must cultivate an integrationist lens for the benefit of migrant children, aiming for immediate impact while cognizant of the future dividend found in healthy and thriving communities. Various research shows that the mitigation of traumatic experiences has its roots in secure and safe attachments. A child’s ability to stop time to find respite and healing during a treacherous journey provides a poignant reminder, compelling us to preserve and celebrate the resilience that inspires our work. Wendy Young, JD, MA President Kids in Need of Defense (KIND) Washington, DC, USA www.supportkind.org Jasiel Fernández, MA Deputy Director of Social Services Kids in Need of Defense (KIND) By Celeste Bilbao-Joseph

Transgender individuals suffer from high levels of discrimination, oppression and social isolation, associated with poor mental and sexual health. Social exclusion also leads to low levels of education, high unemployment and poverty. The experience of Trans Latinas in Canada is further complicated by their histories as migrants. They are affected by transphobia and neo-colonial racialization throughout their lives – in their communities of origin, during the migration process itself, and upon arrival in Canada. Leaving behind contexts of radical exclusion, Trans Latinas hope to find basic rights in Canada but continue to experience exclusion based on their gender, ethnicity, lived trauma, and migratory status. This radical socio-economic exclusion has a powerful dehumanizing effect. The complex experiences of trans immigrants require an approach that emphasizes and addresses the intersectional nature of the challenges and systems of oppression brought on by their gender and migrant identities. Recognizing these needs, in 2018, we developed a partnership between researchers at GloMHI, the University of Toronto, the Centre for Spanish Speaking People, and members of the Toronto Trans Latina community to launch the 'Trans Latinas Overcoming Barriers' (TLRB) project. The project comprised 12 biweekly workshops – with sessions on self-care, social integration, and economic inclusion – and 6 monthly peer-led Self-Care/Peer/Advocacy (SPA) sessions, to:

Year 2 of the project launched in 2019. Peer leaders coordinated and facilitated Trans SPA sessions with the support of an Advisory Committee formed by part of the research team from Year 1. We expanded the target population to all Trans folks (not gender-specific), focusing on all racialized community members (not just Latinxs) who are often also immigrants. It is important to highlight that our TLRB project was born purely from the needs of the community – a community that was treated as invisible and felt underserved and unloved. Joining in our shared humanity, our academic team and trans community partners created this intervention with the goal of challenging the inequities and social injustices that the migrant trans community suffers. We aimed to decrease these inequities by co-creating a unique place in the world and a unique moment in time where trans migrants could thrive, be fulfilled and happy. By focusing on needs identified by our trans community partners, we strongly believe that the tools, knowledge, and skills created in the TLRB project can help remove some of the systemic obstacles trans individuals face and may empower participants to continue this work themselves. It is our hope that this model can be modified to different cultures or settings across Canada, Latin America, and beyond, in order to continue our mission of working as partners with the trans community and contributing to its social and economic inclusion, aiming at achieving our common goal, social justice. Celeste Bilbao-Joseph Mental Health Clinician Center for the Spanish Speaking Peoples (CSSP) Toronto, Ontario, Canada By Professor David Scott FitzGerald

Most refugees do not have a legal way of reaching safety in the rich democracies of the Global North. There is no legal line where they can register and wait as their number advances. Obtaining a resettlement slot is like winning the lottery. The only realistic way to reach the Global North is to reach its territory and then ask for asylum. The core of the asylum regime is the principle of non-refoulement that prohibits governments from sending refugees back to their persecutors. Governments attempt to evade this legal obligation, to which they have explicitly agreed, by manipulating territoriality. A remote control strategy of “extra-territorialization” pushes border control functions hundreds or even thousands of kilometers beyond the state’s territory. An architecture of repulsion based on cages, domes, buffers, moats, and barbicans keeps out asylum seekers and other migrants. Australia, Canada, the United States, and the European Union have converging policies of remote control to keep asylum seekers away from their territories. Simultaneously, these states restrict access to asylum and other rights enjoyed by virtue of presence on a state’s territory, by making micro-distinctions down to the meter at the border line in a process of “hyper-territorialization.” “Refuge Beyond Reach: How Rich Democracies Repel Asylum Seekers” (Oxford University Press, 2019) analyzes different forms of remote control, going back to the their 1930s origins, explains how they work together as a system of control, and establishes the conditions that enable or constrain them in practice. It argues that foreign policy issue linkages and transnational advocacy networks promoting a humanitarian norm that is less susceptible to the legal manipulation of territoriality constrains remote controls more than the law itself. The degree of constraint varies widely by the technique of remote control. Psychologists have shown that people are more likely to mobilize around saving the lives of identifiable individuals in close proximity. Remote control policies by design or effect thwart that humanitarian impulse. Like nation-states, medical institutions can evade their obligations by repelling those in need from entering shared spaces. Sociologist Alejandro Portes describes how U.S. hospitals often deliberately create obstacles between sick people seeking health care and the doctors who have taken the Hippocratic Oath to render aid. Only patients with the resources and insurance to get past a hospital’s clerical gatekeepers and physical barriers surrounding the examination room can put themselves in a space where the doctor’s norm to render aid is activated. This “Hippocratic bubble” is created by the same logic of controlling space that puts up barriers to keep out asylum seekers. Ironically, the healing temple where Hippocrates founded modern medicine stands on the Greek island of Kos across the water from the beach where three-year-old Kurdish Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi’s body washed up in 2015. The world’s collective failure to shelter refugees from the Syrian civil war produced its most visible icon of despair when a toddler died at the edge of the Hippocratic bubble. David Scott FitzGerald, PhD Professor, Department of Sociology Gildred Chair in U.S.-Mexican Relations Co-Director, Center for Comparative Immigration Studies UC San Diego, CA, USA By Professor Warren Dodd and Ms Amy Kipp

Honduras is a Central American country with a population of 9 million, with approximately 40 percent of people living in rural areas. In recent years, however, migration to urban centres and international destinations has increased. The decision to migrate is often related to the lack of security experienced by individuals and households. Security includes both “freedom from fear” and “freedom from want.” People may migrate trying to avoid threats of physical violence or seeking better opportunities for education and employment. This strategy is particularly common among educated youth. To further understand this trend, we spoke with 60 students graduating from a secondary school in the rural municipality of Yorito, Honduras. During a classroom activity, participants shared their future plans. The results of this study were presented in a paper recently published in Migration and Development. Almost all (97%) participants indicated that they planned to move away from Yorito, following graduation. The majority of students shared a similar motivation for wanting to migrate, namely the lack of socioeconomic opportunities in the region. For example, an 18-year old female participant saw the lack of local employment opportunities as well as limited investment in their community as creating conditions that made it difficult for educated young people to remain in the area. She explained: “Unfortunately, there are few job opportunities given that our community is very underdeveloped. As a result, there are few career options.” Some students viewed migration as an opportunity to provide economic support to their families. “I would like to leave to find new opportunities so that I no longer depend on my mother and can support her,” said a male participant. While migration can improve personal and household security in the region, this comes at a significant societal cost. The fact that virtually all graduating students plan to migrate is alarming, as the outmigration of educated, young people has serious social and economic implications for rural communities. With most young people leaving, communities lose the social and economic leaders of tomorrow, including educators, health care professionals, agricultural workers, and small business owners, among others. Investment in the rural areas of Central America, including investment in agriculture, technology, infrastructure, social programming, and professional capacity development, could play an important role in creating local employment opportunities for educated youth and replace outmigration as the main livelihood strategy. Instead, unfortunately, these needs and opportunities clash with renewed threats by the U.S. government to cut foreign aid to Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, combined with a lack of willingness and capacity by national governments in the region to promote such investments. Thus, in the foreseeable future, there will be few opportunities for educated youth from rural areas in Central America to enhance individual and household security by remaining in their communities. The flux of migrants from the region to North America will continue and possibly increase. Warren Dodd, PhD Assistant Professor School of Public Health and Health Systems Faculty of Applied Health Sciences University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Amy Kipp, MA Research Associate School of Public Health and Health Systems Faculty of Applied Health Sciences University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario, Canada |

Global Migration & Health Initiative - Copyright © 2015-22

RSS Feed

RSS Feed